by Patrick L. Barry and Dr. Tony Phillips

A robotic submarine plunges into the dark ocean of a distant world, beaming back humanity's first views from an alien ocean. The craft's floodlights pierce the silty water, searching for the first, historic sign of extraterrestrial life.

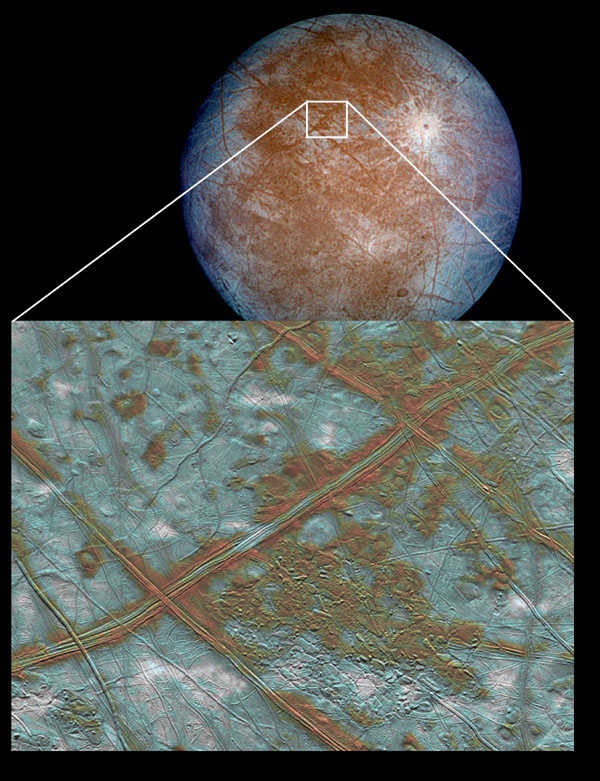

Such a scenario may not be as fantastic as it sounds. Many scientists believe that Jupiter's moon Europa conceals a vast ocean under its icy crust. If so, heat from the moon's interior-which would keep the ocean from freezing solid-may also drive subaquatic volcanoes and hydrothermal vents. On Earth, such deep-sea vents provide chemical energy for ecosystems that thrive without sunlight, and some scientists even suggest that Earthly life first got started around these vents.

So a warm Europan ocean spotted with thermal vents could be a natural incubator for life. That's why some scientists hope that someday we will send a probe to Europa that could bore through the ice and explore the ocean below like a submarine.

To plan for such a mission, scientists would first need to put a camera in orbit around Europa. By looking for places where water has welled up to fill the spindly cracks that riddle Europa's surface, scientists can estimate where the ice is thinnest-and thus easiest to bore through.

That mission scenario presents a problem, though. Europa orbits Jupiter inside the giant planet's punishing radiation belts. Continuous exposure to such high radiation would damage today's scientific cameras, making the information they gather less reliable and perhaps ruining them completely.

That's why NASA is designing a more radiation-tolerant CCD that could be used on a mapping mission to Europa. A CCD (short for "charge-coupled device") is a digital camera's chip-like core, which converts light into electric signals.

"We've seen the effects of this radiation during the Galileo mission to Jupiter," says JPL's Andy Collins, principal investigator for the Planetary Imager Project. "Galileo has orbited Jupiter for many years, dipping inside the radiation belts only for brief intervals. Even so," he says, "we've seen clear signs of damage to its instruments."

By using the hardier CCD's developed by the Planetary Imager Project, a future probe could remain in Jupiter's radiation belts for many months, gathering the maps scientists will need to finally get a peek behind Europa's icy veil. And who knows, maybe there will be something peeking back!

To learn more about the Galileo mission to the Jupiter system, visit http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/galileo/ . For children, a fun, interactive "Pixel This!" game at http://spaceplace.nasa.gov/p_imager/pixel_this.htm introduces CCDs and how a really tough one will be needed for a future mission to Europa.

This article was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.